In 2023, I read about women who achieved what they did against great odds for their time.

I read graphic novels, thanks to my husband, who brings these delights home. One about a woman who painted when women were not expected do so, Artemisia Gentileschi, (1593 – 1652) and one about Charlotte Bronte’s childhood. (Spoiler about the Brontes: almost everyone dies.) The third was especially interesting, because we saw some of her short films at 2023’s silent film festival..

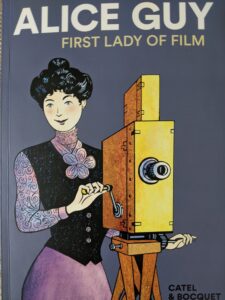

Alice Guy: First Lady of Film, art by Catel Muller, written by José-Louis Bocquet, translated from the French by Edward Gauvin, 2022

Born in France in 1873, Guy made her first films in Paris in 1896, one year after the Lumiere brothers famously displayed their invention. We saw one of those at the festival, “The Cabbage Fairy,” in which real babies are plucked from a cabbage patch. Hysterical. One presumes no babies were harmed in the making of the film. She made 18 short films a year after that and later longer films, wrote scripts and directed. Much has been lost, but over 60 of her films remain. The French are restoring her to her proper place, have several books about her. She was an endlessly energetic filmmaker, undaunted by difficulties.

Miss Grief and Other Stories, Constance Fenimore Woolson, Edited by Anne Boyd Rioux, Norton, 2016

Constance Fenimore Woolson: Portrait of a Lady Novelist, by Anne Boyd Rioux, also 2016, was named one of the ten best books of the year by the Chicago Tribune.

Woolson wrote in the 1860s – 1890s, until her death at 53, which may have been suicide. She was popular in her time, published five novels and her short stories appeared in Harper’s and the Atlantic. Male critics thought she was out of her lane. Women had no business with realism or unhappy endings, and she wrote both. She suffered early deafness and depression, afflictions her father also experienced. Born in New Hampshire in 1840, Woolson died in Venice in 1894. A grandniece of James Fenimore Cooper, she became friends with Henry James in Europe.

Woolson wrote about the Great Lakes region, the American South and American expatriates in Europe—all places she lived. She had a gift for evoking a sense of place and in America visited wild and little populated locations. The Great Lakes stories explore marshlands and their few inhabitants, environments that no longer exist.

One of her Southern stories, “Rodman the Keeper,” evokes a melancholy regard for the post-Civil War South from a Northern perspective. Rodman is a Union officer left as keeper of a cemetery where 14,321 union soldiers are buried. The recently defeated Southerners shun him. No one visits the cemetery.

Rodman spends his own money for a second flag, “so that, rain or not, the colors should float over the dead. This was not patriotism so called, or rather miscalled, it was not sentimental fancy, it was not zeal or triumph; it was simply a sense of the fitness of things, a conscientiousness which had in it nothing of religion, unless indeed a man’s endeavor to live up to his own ideal of his duty be a religion.”

He maintains his habits in the South, getting in “Irish potatoes, corned beef, wheaten bread, butter and coffee; for he would not eat the hot biscuits, the corn-cake, the bacon and hominy of the country…”

Rodman comes upon a seriously ill Southerner in the ruins of his family’s mansion, with an elderly Negro servant, former slave, taking care of him. He brings the man to his own quarters, where there is heat, fresh water and food, the old servant assisting. The union officer and Southern aristocrat have had similar educations. We enjoy the conversations the two have, even when painful. A Southern family member arrives, appalled at finding him on enemy ground, and takes the ill man away.

Rodman returns to his solitary life, on Decoration Day wakes to the sound of people. The black residents have come en masse to place flowers on 14,321 graves.

From “A Florentine Experiment,” written while living in Europe:

Morgan ruminates on Miss Stowe’s intentions: “He made up his mind that her aim was to excite remark in their circle; there was probably someone in that circle who was to be stimulated by a little wholesome jealousy. It was an ancient and commonplace method and he had not thought her commonplace. But human nature at heart is but a commonplace affair, after all, and the methods and motives of the world have not altered much, in spite of the gray lapse of ages.”

In the Michelangelo chapel of San Lorenzo, Morgan asks Miss Stowe about the marble statues: “What do they mean?” he said. “Tell me.”

“They mean fate, our sad human fate: the beautiful Dawn in all the pain of waking; the stern determination of the Day; the recognition of failure in Evening; and the lassitude of dreary, hopeless sleep in Night. It is one way of looking at life.”

How sad that these two extraordinary women were lost: what a joy that they’ve been found again, even if I am late to the party. Much more of Fenimore Woolson’s writing is now available.